-

Breaking the habit

February 18, 2022 @ 1:31pm – San Francisco, CA We learned from a new angle just how wondrous a thing the brain is. A one-litre, liquid-cooled, three-dimensional computer. Unbelievable processing power, unbelievably compressed, unbelievable energy efficiency, no overheating. The whole thing running on twenty-five watts — one dim light bulb.”

Ian McEwan, Machines Like Me

When you have a bad habit, it becomes very easy to do things you don’t want to do, like staying up late watching YouTube.

But when consciously created, a habit can make it easy to do something you want to do, like eat healthier or go to bed a bit earlier.

Habits rewire your brain and eventually even change your identity. James Clear writes about this in his popular self-help book Atomic Habits (2018). You don’t just go to the gym every Monday, you become the type of person who does so.

A habit helps you to show up even when you have temporarily lost interest, motivation or willpower. On a particularly cold night, my swim coach admitted that ‘some nights all that’s left is the habit.’ That could sound a bit sad, but sometimes that’s the difference between sticking at something and giving up entirely.

Habits seem to work so well because humans are habitual by nature. When certain brain circuits are triggered, we react the same way again and again. Most of our movements are habitual and automatic. The way we breathe, stand, talk, scratch, itch, whistle. Our preferences repeat too, like which clothes we select to wear or which yoga mat we like to sit on. When so much of who we are, and what we do is a habit, the harder it is to notice.

And so, the danger of introducing new habits, is that although life may get easier and more efficient, we may also become even more stilted, predictable and mechanical than we already tend to be.

A man decides to run three times a week. Over the course of year his physical and mental health improve. He finds that he has more energy and a brighter outlook on life. But even this healthy habit can become unhealthy. His unconscious desire for perfection means he becomes irritated and frustrated when the weather is bad or his stats aren’t improving. He denies spontaneous impulses to try out different, more interesting routes. He turns down social invites to keep his streak going. And eventually gets injured after ignoring obvious signals from his body to mix things up or to rest.

We want to hammer our lives like a nail, tag it, stereotype it or cram it into a category.

But life isn’t mechanical.

Iain McGilchrist writes that “The only things in the universe that are machine-like are the few lumps of metal we have created in the last 300 years.”

This might be why mechanical things often fail or break in dreams.

So before you install a new habit, see how it feels to eat your dinner in a different place, at a different time or to skip it entirely. Maybe it’s worth removing a something habitual, before adding more.

When we gain the ability to hold our habits lightly, we find freedom, maybe the most important thing in life, or at least much more important than a healthy meal or some saved time.

This is the 100th post on Buddha.Bike

-

Claws and teeth

June 5 @ 12:08pm – Hawthorn, Australia Heating up

We were born to work together like feet, hands and eyes, like the two rows of teeth, upper and lower. To obstruct each other is unnatural. To feel anger at someone, to turn your back on him: these are unnatural. To feel anger at someone, to turn your back on him: these are obstructions – Marcus Aurelius

Why does anger exist? “Fear tells us what to avoid; anger tells us what to resist. Both of these emotions exist to keep us from dying, from getting hurt, from losing energy.”1 When “anger is roused…it tries to push away and eliminate whatever it is that’s unpleasant.”2

When you have anger, passion, fear, breath can never remain normal. A little harder, faster. Also heat, palpitation at the biochemical level. – S.N. Goenka

Minor irritations can lead to anger. I know that when I’m late for something and I’m rushing around, it’s easy for lots of irritations to stack on top of each other, and I’m more likely to get angry. When I’m swimming laps, leaking goggles, missing instructions or losing track of my time all start as minor irritations but can quickly build up into anger too.

In order for a fight to happen, at least one person needs to take it personally. Just like pain needs to be personal, so does anger.

Everyone expresses anger differently. Some will express it immediately and then get on with their day. Others don’t acknowledge their anger, but will take it out on their kids, or an untidy house.

Anger, like any strong emotion, literally distorts your perception. Anger can easily spill out into the environment. This is what people mean when they say ‘projecting’. You are sending out your anger, and suddenly all the cars around you are angry, everything is angry but you. Your unclaimed anger might appear as a monster in a nightmare.

I seem to care a lot about fairness (in a subjective, relative sense). For me, the thought ‘that’s not fair!’ is very often associated with a feeling of anger. Perhaps the more righteous you are as a person, the more angry you’ll tend to be.

A person who is never angry will not be able to love either. – Osho

Anger is hot. Resentment is cold. Resentment is pickled anger. Fritz Perls, founder of Gestalt therapy, believed “the key to resolving resentment…was expressing one’s anger.”3

Another grotesque side product of suppressing anger is passive aggression. Those little snarky comments we can make sometimes are like steam leaking out of clamped down pot.

You can hold a grudge for decades, but the actual emotion of anger leaves your body very quickly. “It takes less than 90 seconds for me to think a negative thought, have a negative emotion, run the physiological response, have it flood through me and flush out of me.”4

Cooling down

It is very difficult to observe anger as anger – abstract anger – S.N. Goenka

In the Tibetan Buddhist system, anger is the same substance as clarity and intelligence, which is an interesting comparison. When you think of anger as a form of energy, it’s easier to see that it is “free of any problems, except the problems we create out of fear of that energy.”5

There’s lots of ways to express your anger in a safe way. Turn it into aggression in the gym. Do some primal screams. Anything but act on it blindly.

Exercise seems to help, since we can’t really exercise angrily, but we can exercise aggressively.

You can write it down. What was the thing that made you angry? Or what is the angry thought you’re having? I’ll write down “I have no time” or “This is a waste of time” and an angry face 😡 next to it.

The better you can deal with anger, the more responsibility you have to do so.

Anger is given to us like claws and teeth, to defend ourselves and is vitally important. We need rage and anger. But Jung taught us to first learn to control it and then to use it in a controlled way. Let it out, but let it out so that you could stop any minute if you wanted to. – Marie Von Franz

- Ego – Peter Baumann ↩︎

- The Practice of Not Thinking – Ryunosuke Koike ↩︎

- https://www.anilthomasgestalt.com/about-fritz ↩︎

- https://www.youtube.com/clip/UgkxLhPBmIvO28k9YC8Z81UMLP_ayXZGV8kT ↩︎

- https://selfdefinition.org/tibetan/articles/mindfulness-anger-management.htm ↩︎

-

Sliding doors

February 19, 2022 @ 11:53 am – Petaluma, CA I have found life to be too short to be preoccupied with pain from the past. – Jill Bolte Taylor

On a recent meditation retreat, I spent the first few days living in the past. I finished each day in a fog, feeling like I had recounted every single missed opportunity and disappointment I’d ever experienced.

No matter what technique I used to calm down, my mind would find a new thing to feel sorry about. Eventually, it relaxed a bit and I could enjoy the last few days without too much rumination.

When we clutch hold of missed opportunities or ‘what ifs’, we can’t help but feel miserable. It’s almost like the closer things were to playing out differently, the more pain and regret we feel.

Yet, our future is always changing based on the choices that we are making in the present.

One place to see these probabilities play out is in our dreams.

There are many different beliefs and theories about what the images in our dreams mean. A Jungian analyst might see a car crash as a metaphor or a symbol representing an inner dynamic. A Theosophist might see a premonition, a warning to drive more carefully. Or for the majority of us, it’s random, meaningless and already half forgotten.

But what if these images reflect real possibilities? I’m not talking about the dream with the spaceship or the fire-breathing dragon. I mean the dream where you are living in a nicer house, or a different country. Banal stuff. Things that could have, or might still happen to us, depending on chance or the decisions we make.

For example, in a recent dream, I was:

- Camping with an old friend from High School

- Struggling to ride a bike

- Living somewhere in Colorado

- In a very senior, chaotic role at my company

Choosing one job over another, a promotion swinging my way, a lower level of motivation, never leaving a place I used to live. These are all probable, plausible alternatives to my life. In a metaphorical sense, they are forked code, glimpses of parallel universes.

A sliding door dream doesn’t neccasarily paint a picture of a better life, just of a slightly different one. This can open us to new opportunities and perspectives.

And still, even if you choose to remain fixated on the past, consider that other versions of yourselves are living different, perhaps happier lifetimes, in your dreams.

Read this post on Substack

-

A study in Frustration

Screenshot from The Simpsons episode ‘Homer’s Enemy’ © 1997 Fox Broadcasting Company “Suffering is the rejection of reality” – Yuval Noah Harari

Thy right is to work only, but never to its fruits; let the fruit of action be not thy motive, nor let thy attachment be to inaction.” – Bhagavad Gita

Why are some people more easily frustrated than others?

It could be that they have especially dodgy wi-fi connections or bad traffic on their way to work.

It could be their disposition, conditioning or upbringing.

But maybe it’s because of their internal rules about the world. Beliefs about how things ought to be.

When these assumptions clash with reality, they get frustrated.

To see how these sorts of beliefs can backfire, let’s look at Frank Grimes, a hapless character from The Simpsons, the episode ‘Homer’s Enemy’.

Frank is this really square, serious, buttoned up guy “who’s earned everything the hard way.” He’s a ‘real life, normal person’ who’s just working hard and struggling through life.

The joke of this episode is to have Frank start working at the power plant alongside Homer. Obviously opposite of Frank, Homer is a slacker, constantly failing to do his job properly, yet managing to coast through life. Homer can’t help but irritate Frank, who eventually becomes his sworn enemy.

As Frank settles into his new job, you can tell he’s a model worker who doesn’t have time for messing about. After perfunctory introductions he dismisses Lenny and Karl, saying “I’m sure you all have a lot of work to do.” Homer irritates him immediately, by knocking over his perfectly ordered pencils. Frank believes a good worker has a nice clean desk and doesn’t waste time with chit-chat. This sort of belief might help him feel like he’s had a productive day at the office, but it doesn’t leave much time for personal connections.

Frank is appalled at Homer’s indifference and sloppy shortcuts. When alarms are ringing in Homer’s control room, Frank has to point it out. He starts to gossip, “I saw him asleep in a radiation suit” and “I’ve never seen him do any work”. Homer doesn’t fit into what Frank believes a Safety inspector should look like, and the result is resentment: “That’s the man who’s in charge of our safety?”

When Homer nearly drinks from a beaker of acid, Frank’s beliefs compel him to intervene. Thinking fast and doing the right thing saved Homer’s life. But along with those good morals is a big dose of righteousness. He can’t help but give him a lecture. “Don’t you realise how close you came to killing yourself?” In Frank’s world, people ought to be cautious and careful. He feels that he needs to step up, because no one else seems to care.

Frank’s resentment goes into top gear when he visits Homer’s home. He’s stunned to discover that Homer has been living in a ‘mansion’. Homer has everything that Frank wants, but doesn’t have. Deep down Frank believes that only those who ‘work hard every day’ deserve a ‘dream house, two cars’ and ‘beautiful wife’. The result is the unpleasant taste of bitterness and more resentment.

Frank only lasts an episode. He winds up electrocuting himself, yep, you guessed it, to prove a point. He couldn’t survive that particular clash with reality. Josh Weinstein, Simpsons producer, expressed regret for killing him off so early but admitted that “we took a certain sadistic glee in his downfall. He was such a righteous person, and that somehow made his demise more satisfying.”

Frank also inspired an interesting mix of reactions amongst fans too. Many related to his realistic struggle while others just wanted him gone. Everyone seemed to take away a slightly different lesson from the episode. Here are some comments from a YouTube clip:

- “The less you care about life the more you gain.”

- “Found it funny as a kid. Now it’s realistically painful. Like I totally understand Frank’s frustration now that I’m adulting”

- “Frank no doubt deserved a better life, but he blew his chance to try and make at least one friend.”

- “our modern day Job(from the Bible)”

- “Dumb lazy people = succeed Hard workers = failures”

- “people will always prefer the fun-loving over the miserable man.”

- “Life isn’t fair, Frank.”

I feel bad for Frank. He had a point, but his downfall came from clinging too tightly to it. His rigid beliefs about what a good person should look like, and what a good person deserves, only fueled his misery and suffering. He couldn’t find a balance between his particular internal code of perfection and the real dysfunction around him.

But someone like Frank needn’t abandon their integrity or work ethic. They shouldn’t have to switch off their brain like Homer or melt down into caustic cynicism. What would help is patience (the best remedy for anger) and abiding by your inner rules a little more lightly. Neither squeezing life with a death grip, or giving up on it, but simply allowing it to happen.

Read this post on Substack

-

Abstractified

November 19, 2024 @ 6:31pm – Hawthorn, Victoria, Australia What I like about Temple Grandin is she gets to the point.

In “Animals in Translation”, she doesn’t spend long digging into the science, research studies or history behind a fact. She’ll just say something like “in my experience dogs do not like Halloween costumes.”

And she’s probably right.

She likes to use heuristics like “the more Wolfie a dog looks, the more Wolfie it acts” and she’s not afraid of wading into un-researched areas either, “I expect we’ll find that dogs make humans into nicer people and better parents.”

As I read on, I was surprised not only how willing I was to give her the benefit of doubt, but also how refreshing her writing felt. Why was that?

I mean, I don’t even own a dog.

One reason her writing stands out might be because she’s autistic. Temple is highly functioning, but clearly looks at the world differently. One example of this is how she sees things most people don’t. In her work with livestock, she created a checklist of 18 ‘tiny details that scare farm animals’. For her, and to a 1200lb Angus, a ‘sparkling reflection on a puddle’ is really distracting, something even seasoned farmers weren’t noticing.

Secondly, she doesn’t signal. Usually in a popular science book like this, the author is subtly signalling all sorts of things like that they’re smart, woke, a New Yorker, a creative or that they’ve read a ton of books. Everyone does this to some degree. Publishing a book itself is usually about establishing some degree of credibility and authority. It’s actually so prevalent that it’s hard to notice, until you read a book like Animals that is completely devoid of it. It’s not that she doesn’t have an ego, or a point of view, she just doesn’t seem to care how she comes across. She is simply trying to communicate important things to know about animals. Yes, really. Even when she is considering something controversial like whether humans should eat meat or not, she’ll talk about the idea purely on its merits, something pretty much no one does.

Lastly, Grandin avoids the usual frameworks and buzzwords that are so common in pop science books. In fact, she views abstract thinking as a big blind spot for us ‘normal’ people.

“Unfortunately, when it comes to dealing with animals, all normal human beings are too absractified, even the people who are hands on. That’s because people aren’t just abstract in their thinking, they’re abstract in their seeing and hearing. Normal human beings are abstractified in their sensory perceptions as well as their thoughts. That’s why the workers at the facility where the cattle wouldn’t go inside a dark building couldn’t figure out what the problem was. They weren’t seeing the setup as it actually existed; they were seeing the abstract, generalized concept of the setup they had inside their heads. In their minds their facility was identical to every other facility in the industry, and on paper it was identical. But in real life it was different, and they couldn’t see it. I’m not just talking about management. The guys in the yard, who were there working with the animals, trying to get them to walk inside the building, couldn’t see it, either.”

Abstraction is hard to avoid, especially in knowledge work that involves complex, messy problems that span code, relationships, digital systems and physical environments.

Even so, I’d like to think of Temple barging into a meeting, covered in mud, sweeping all the post-its aside, clearing the diagrams off the whiteboard and saying ‘what the hell are you guys doing here?’

In 2023, I wrote Keeping in Touch, inspired by Temple’s first book, Thinking in Pictures

-

Designing with concepts

March 20, 2025 @ 7.32pm – Hawthorn, Victoria, Australia In his book The Essence of Software: Why Concepts Matter for Great Design, author Daniel Jackson says that all apps are made up of collections of “concepts” each a “self-contained unit of functionality.”

A concept isn’t exactly a design pattern, feature or job to be done. So, what is it?

“You’re already familiar with many concepts, and know how to interact with them. You know how to place a phone call or make a restaurant reservation, how to upvote a comment in a social media forum and how to organize files in a folder.”

So when you write an email in Gmail, or message a friend on WhatsApp, you’re not just scrolling screens and tapping buttons, you’re relying on these invisible “concepts” like Inbox and Conversations.

Concepts are everywhere, characterizing every piece of software.

Another concept you’re probably familiar with is a comment. You might find comments on a NYT Cooking recipe, a line in a Google Doc or a video on Meta. A comment lets users to respond to something specific. Like a comment, but a bit more specific, an upvote on Reddit lets users to show they support a post, making it more visible to other members.

If you’re responsible for designing software, you’re likely already dealing with lots of concepts that were “invented by someone at some time, for some purpose… (and have) undergone extensive development and refinement over time.”

Well designed concepts means better usability

‘So what?’ you’re thinking. I’m a designer, I’m focused on real problems like usability, not abstract concepts.

Well, what makes software difficult to use? Sometimes it’s because features are missing or hard to find but usually (it only takes one user testing session to learn this), it’s because “the user has a mental model that is incorrect—that is, incompatible with the mental model of the designer and implementer of the software.”

Or in other words, the user experiences bad design.

We can design better software when we understand how our users think about the software – their mental models. And likewise, “An app whose concepts are familiar and well designed is likely to be easy to use, so long as its concepts are represented faithfully in the user interface and programmed correctly. In contrast, an app whose concepts are complex or clunky is unlikely to work well, no matter how fancy the presentation or clever the algorithms.

‘Style’ – A closer look at a word processing concept

I first learned about concepts from Daniel Jackson years ago. The thinking resonated with me, but as a product designer I struggled to put it to use. Since concepts ‘have no visible form, they’re rather abstract’, it’s easy to overlook and dismiss them.

One simple way to work with concepts is to compare how they’ve been expressed in similar apps. Take word processing for example. It turns out Microsoft Word & Apple Notes share lots of the same concepts like paragraph, format and style.

In Notes, an app created by Apple to help “jot down quick thoughts”, clicking a button in the toolbar opens a menu with 9 preset styles.

Notes: Click anywhere in the text you want to format, click “Aa”, then choose a style. In Word, there’s also a similar Style menu in the Toolbar, but instead of 9, there’s 16 preset styles. When you resize the window, more styles become accessible in a visual ‘Style Gallery’. Fancy. There’s also a side panel so you can see all the styles while you type as well as heavy duty style management in settings.

Word: Select the text you want to format, and then click the style you want in the Styles gallery.Style is a foundational concept, which is why it appears in both apps and works in pretty similar ways. But small differences point to different product decisions, target users, and even company values.

Designing with concepts

Aside from discovering concepts in apps you use, here are a few ways to bring concepts into the actual design process.

- The less the better: Aim to use the smallest set of concepts users need to get the job done. Simple doesn’t necessarily mean less functionality or more white space. It’s true that some of the best designed apps are simple, but they are simple because they use a small number of elegant concepts – or paraphrasing Gall’s law, “evolved from a simple system that worked.”

- Don’t overload: If you’re thinking of introducing a new concept into your product, always make sure it has a clear “purpose”. Don’t overload a concept to make it try and solve lots of different problems at once. In Word, buttons for formatting text appear near to the Style panel (because that’s where one might expect them to be) but they aren’t all mixed up in same menu.

- Where are concepts failing? When you test a design with a user, consider if they are having trouble with a particular interface element or bit of content, or if there might be a broader issue with how concepts have been designed and implemented.

UI widgets don’t determine the success of a successful product, well designed concepts do. When we work with them directly, we can design systems that are more enjoyable, learnable and effective for the user.

Want to learn more? Daniel Jackson has created a lot of content on this subject:

- Short read: Software = Concepts (6 min read)

- Watch: What makes software innovations succeed? Maybe not what you think. (13:30)

- Long read: The Essence of Software: Why Concepts Matter for Great Design (336 pages)

Read this post on Substack

-

Taking meditation seriously

July 12, 2024 @ 12:22pm – Mission Dolores Basilica, CA As soon as one believes a doctrine of any sort, or assumes certitude, one stops thinking about that aspect of existence. – Robert Anton Wilson

Belief is a toxic and dangerous attitude toward reality. After all, if it’s there it doesn’t require your belief- and if it’s not there why should you believe in it? – Terrence McKenna

I recently finished my second 10-day silent Vipassana retreat.

As I said my goodbyes, I got into conversation with Vishal, the man I’d been sitting next to in the meditation hall every day. Since there’s no talking or eye-contact allowed, the other meditators (about 24 men and 24 women) are more like blurry shapes of energy than actual personalities. You can’t help but think about what they are like in the outside world, but we’re reminded that this is just another distraction.

Yet, with only occasionally glances at him in my peripheral, I’d noticed his quiet determination. Compared to others, he took every sitting as seriously as possible. Sometimes you can just tell.

When I said this to him, he smiled politely. “You take it seriously too.”

Two years prior, I had signed up and sat my first retreat quite spontaneously. I had no meditation practice or even theoretical knowledge to prepare me. But after a short ‘dark night of the soul’ on Day 3, where I was close to packing my bags, I was suddenly all-in. When the gong was struck at 4am, I didn’t flinch. I was often first in and last out of the hall. I started to deeply enjoy the simple, vegetarian meals. 10 days went by in a blur. On the final day, when ‘noble silence’ was lifted, others came up and congratulated me. “You were sitting like a statue.” “How did you do that?” I felt surprised and sheepish. I didn’t have an answer. I shrugged, “I guess I just took it seriously.”

I shared some of this with Vishal, who nodded. He was tall, and pious looking, with carefully groomed hair. It had been ten years since his last retreat, due to a busy family life, part of the reason he’d tried to make the most out of the last ten days.

“We’re serious because we’ve done this before.”

Due to his beliefs, karma and previous lives explained my disciplined almost reverent approach to meditation, something relatively unfamiliar to me and not connected to my parents or society I grew up in.

In 2023, encouraged by a Taiwanese co-worker, I booked ‘Tour de Taiwan’, and rode around the island in 9 days. Having never visited before, I felt strangely at home with the strange people and places we discovered. Why was that? As we made our way along roads that snaked over mountain passes and rice paddies, familiar faces crossed my mind.

There was Emily, a Creative Director at a tech startup. She was high energy, put on art shows in her spare time and was half Taiwanese. In 2014, after a summer of unsuccessful interviews, my US visitor visa had run out and I’d travelled to London. I was calling her from a loud Starbucks with dodgy wi-fi. But she hired me, and I ended up living in America for the next 6 years.

Four years after that call, another Taiwanese woman took a chance on hiring me, and so I moved from New York to San Francisco. She was also a Creative Director, a single mum, loud, un-filtered and Taiwanese.

At that job, the Taiwanese-American Head of Content, who moonlit as a spin class instructor, encouraged me to sign up for a triathlon, which would become an interest for me over the following years.

Finally, my girlfriend in New York. One weekend we took a trip to upstate New York where we stayed at her family’s house. She was born in the States but her parents were from Taiwan and seemed to be Buddhists by the look of some of the paintings and sculptures dotted around the house. On the way back to the city we stopped at a temple. “We’re not really that serious about it” she said as I gawked at a giant statue of Buddha.

Do these coincidences make me believe in reincarnation? The short answer is no. I like to remain open and flexible in my thinking, which is just not compatible with being certain about stuff like that. But I think it is worthwhile to consider and be grateful for our unique strengths, preferences and affinities – whether you know where they came from or not.

This was also posted on Substack

-

Writing rightly

February 12, 2022 @ 12:56PM – Freeport, Bahamas Last August I posted a note to Substack that outlined my criteria for publishing writing. It should be:

- Interesting (to me)

- Communicated as clearly as I can

- Useful to the reader

I mostly still agree with these but wanted to include my general ethical attitude/approach toward my writing. Here it is, in no particular order.

- I think what I’m writing about is valuable in some way. I wouldn’t share it otherwise.

- My intent therefore is to share that with the reader. That’s basically it. I don’t want to inflame emotions, get you to buy something, troll or make you feel bad.

- I’m not writing for a specific audience.

- Writing is both a means and an end for me.

- I only write what I’d also be comfortable saying, or defending if need be, in person.

- I’ll try to write as clearly as I can. I might use certain words or techniques but my intent is never to manipulate. This is obviously a balancing act, but I’d rather someone be bored and leave than to be tricked.

- I won’t lie or make things up.

- I’m mostly interested in things that you can point to or that seem intuitively right. I don’t make metaphysical claims.

- I want to write as truthfully as I can, but don’t expect exactitudes. That’s not the point of my writing. I might say something like: “we’d be better off drinking water instead of Fanta or whiskey.” One could pick apart that sentence endlessly, but you get what I’m trying to say. This is why I use a lot of words like ‘might’ or ‘probably’. I don’t ever want something I write to be misconstrued or misunderstood as an absolute claim.

- I have opinions but I won’t ever try to force them on you. I try not to write moralistically or judgmentally. For example, although I don’t think it’s a good idea to lie, I will never say that people who lie are evil or that you should never lie. If you want to read what I write, great! If you don’t, great!

- I write about topics I feel confident enough to explore and perhaps offer something valuable to the reader. That said, writing about something doesn’t ever mean I know what I’m talking about.

- Aside from minor tweaks, I don’t dramatically rewrite articles once they’ve been published. If I do seriously change my mind, I might remove the post.

- I occasionally use LLMs for writing support.

- I’m often thinking or relating to real people, places and things that happen in my life, but in almost all cases I won’t use names or details of real people.

- I’ll occasionally quote books or articles, and if I do I’ll make a footnote. But I’m not a good fact-checker. For example, if I quote Socrates or a Wikipedia article, I’m not doing deep research to make sure it’s correct. I go by intuition, and if I feel unsure about the source, I won’t quote it.

-

Are designers making design hard for themselves?

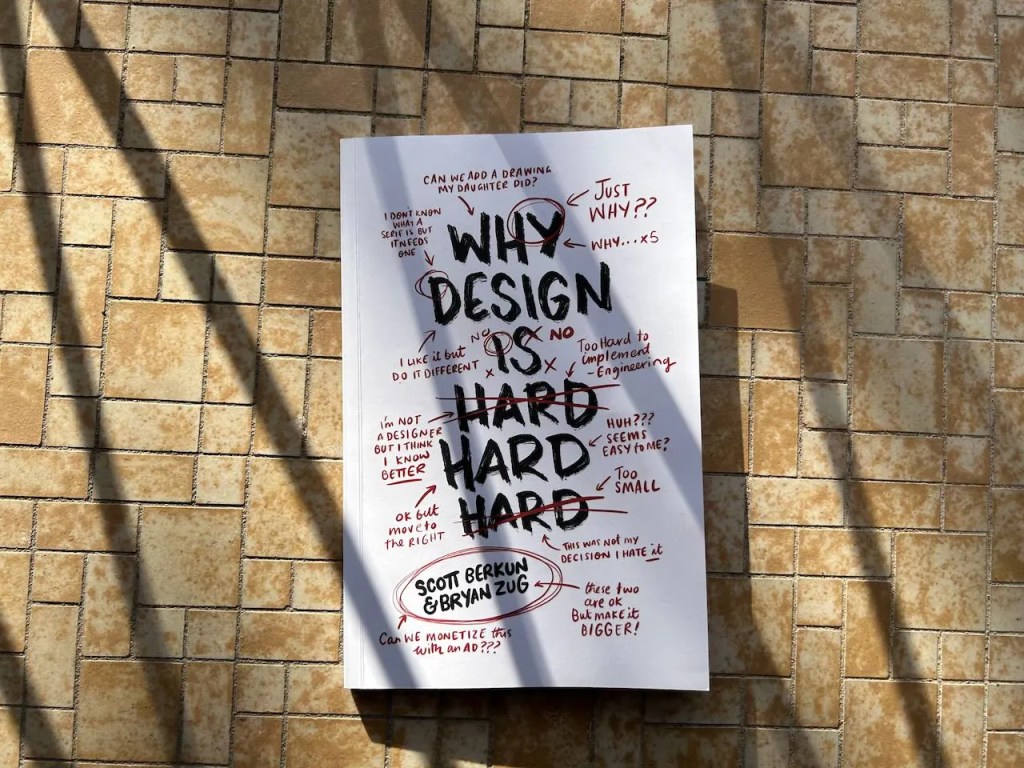

These days, whether it’s gen AI or the overall death of the industry, there’s no shortage of problems flying around for designers. And that’s what I expected to read about when I picked up this short book titled Why Design is Hard.

But instead, I was surprised to see the argument made that design is hard because of an internal problem, rather than an external one; that the profession of design has flaws in how we think about what we do.1

So why is design hard?

- Designers tend to think of design as a solo activity, when it’s clearly not

- Designers tend to think others should just trust their design decisions

- Designers tend to overvalue creativity over bottom-line value for the business

The authors suggest that this type of attitude lands designers (of all levels) in all sorts of trouble. Designers are then surprised when priorities change, offended by constructive critique or resentful that their skills are undervalued or misused.

With a bit of a reality check, designers can stop tripping over themselves and basically get back to designing.

This made me wonder, does every profession struggle with these sorts of attitude problems, or is it only design? Maybe because UX design is a relatively new profession (~100k UX designers in the U.S), it never had much time to solidify its identity, and maybe never will.

The latter half of the book shares a few ideas for ways of working more effectively, particularly focused on designers within large organizations. Here are three that stood out to me:

If you can’t sell it, did you even design it?

In order for your precious work to see the light of day, a designer needs to not only deliver well designed solutions but articulate how the design solves it in a way that is compelling and fosters agreement.2 Like a politician running for election, what’s almost equally important to their ideas is how those ideas are communicated to the voters. For designers, whether it’s explaining a problem, or the results of a successful experiment, if your communication isn’t clear, it’s like it never happened.

The system is working (just not for you)

Have you ever been really surprised by something, like a project that was cancelled at the last minute, or user behavior that clashed with the data? It turns out that often what can seem like stupidity is often a constraint you can’t see.3 Rather than reacting blindly, or waiting for the perfect internal process to materialize, designers should learn to use system thinking (eg. 5 Whys) to help us understand our environment better and anticipate future hiccups.

The one thing designers forget to do…

Let’s face it. No one ever says ‘involve me as late as possible.’4 Whether you are an engineer, or product marketer, a lack of trust and collaboration with design is a recipe for disaster. That’s why it’s critical for designers to shepherd the work through the organization5 and lead their core team along the design process. In a way, showing the same care for coworkers as you might for the end-users you design for. Again, I think soft skills like active listening, empathy & communication do most the heavy lifting here.

Overall, Why Design Is Hard is a short, slightly bitter perspective on how to be effective as a designer (especially within a large organization).

Thankfully, there’s not too many grand proclamations or predictions on the future of design, just good advice on how to stop getting in your own way.

- Why Design Is Hard by Scott Berkun and Bryan Zug ↩︎

- Why Design Is Hard by Scott Berkun and Bryan Zug ↩︎

- Why Design Is Hard by Scott Berkun and Bryan Zug ↩︎

- Why Design Is Hard by Scott Berkun and Bryan Zug ↩︎

- Why Design Is Hard by Scott Berkun and Bryan Zug ↩︎

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.