-

The presenting of intent

Think about the project you’re working on. It’s likely focused on helping our customers achieve some sort of goal effectively. Maybe it’s surfacing a mistake in a pay run, or finding an old bill faster. As the designer, you create solutions to make that goal or outcome a reality. Jared Spool refers to design this way as “the rendering of intent.”

Discovery activities like talking to customers and studying analytics help product teams uncover what is happening, why, and what we’d like to change or do better. That’s the intention bit. Then we need to make that intention real, that’s the rendering. When designers share their work back to their peers and collaborators, we might be talking about drop-downs and buttons, but we are presenting a rendering of intent.

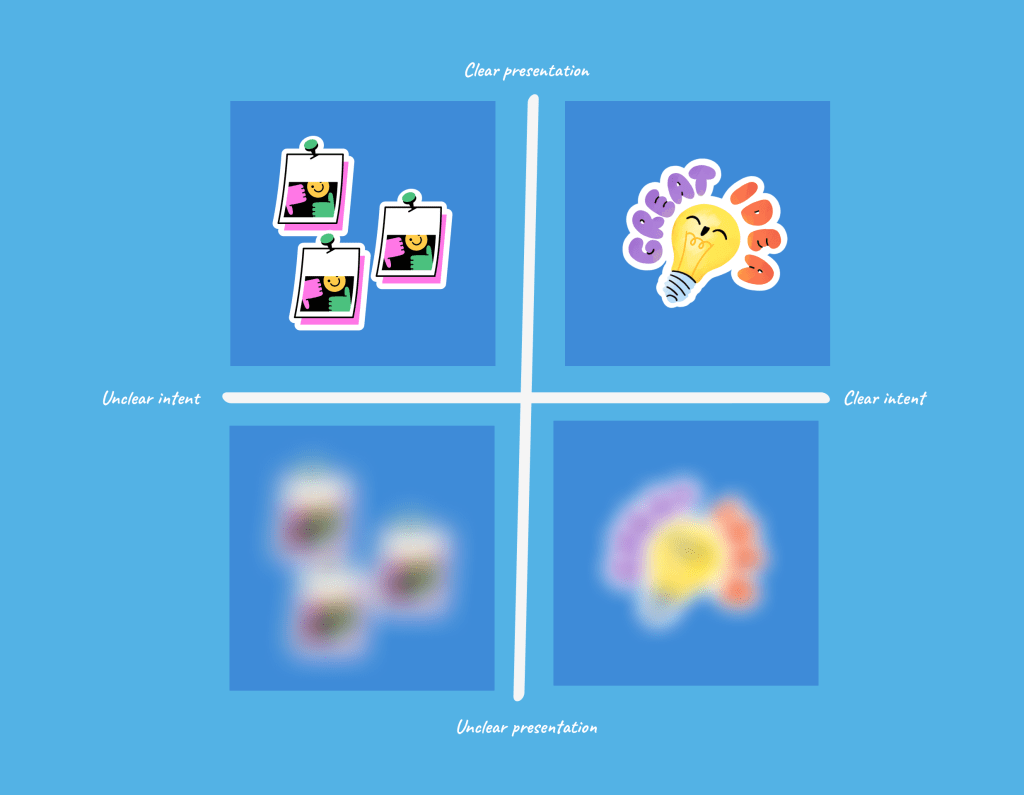

If design is about rendering intent, when we share our work, we should present clearly with strong intention. To explore this concept, let’s look at how it can play out in different scenarios.

Unclear intent, unclear presentation

What it looks like: Without clearly explaining the problem or the solution, your audience will be left wondering exactly what’s going on.

How to fix: Rather than working on the presentation, take a step back and ask yourself “What problem is this solving?” A good next step from there could be to spend time diverging, exploring and thinking through lots of options.

Unclear intent, clear presentation

What it looks like: The prototype is dazzling and everyone want to ship it, but it’s not solving the agreed on problem. You find yourself struggling to answer why you made certain design decisions.

How to fix: Step away from the tools. All the elements are there, but it’s important to return to research or re-interrogate the problem with others around a whiteboard. The design process is your friend here and there’s tons of methods that can be used to look at problem from a new angle.

Clear intent, unclear presentation

What it looks like: When we feel unsure about committing to a specific approach it’s easy to miscommunicate or even over-communicate rather than keeping things simple.

How to fix: Sometimes all it takes is rearranging your slide deck or talking through your work with peers to sharpen what you’re trying to say. These are quick tactical things that are easy to learn. If there’s good thinking, you’re 90% done!

Clear intent, clear presentation

What it looks like: It’s a cliche to say that good design is simple, but it’s true. The designer has done a ton of thinking, exploring and deliberating before settling on a strong approach that they feel confident in explaining (and defending if need be).

How to fix: Not much to fix here, but it’s important for a designer to remain flexible and open to feedback. Rather than dying on a hill, it’s more about having “strong opinions, loosely held”.

To present designs more effectively, aim to make a strong, clear argument for your solution. If you’re in a coaching position, here’s a few ideas I think might help designers:

- Remind the designer that at the end of the day, this is your work, your thinking and we trust you know what’s best.

- There’s usually not one ‘right’ answer – there’s many ways to solve a problem. As long as you think it through, and answer the goal, you should be fine!

-

Fighting the Water

Why is it difficult to relax?

- Relax? Sorry, I’m too busy trying to (dance, box, code, paint, sing…). I’m concentrating on that thing right now, no time to relax thank you very much.

- You can’t fix what you don’t notice, and it can be difficult to notice that you are physically tense or overthinking a movement. For example, I’m always surprised how different I feel after a massage. Maybe I did need that massage after all.

- If relaxing is the goal, trying to relax won’t get you there. Trying by definition is something forced and thought, rather than simply done. To illustrate this difference, consider how it feels to catch something reflexively compared to planning to catch something.

Let’s look at how relaxing might help you swim more easily.

Not pretty I finally relaxed…I actually started to listen to my hands, to what’s going on in the water around me… I began to develop a relationship with the water, as opposed to just fight(ing) the water.

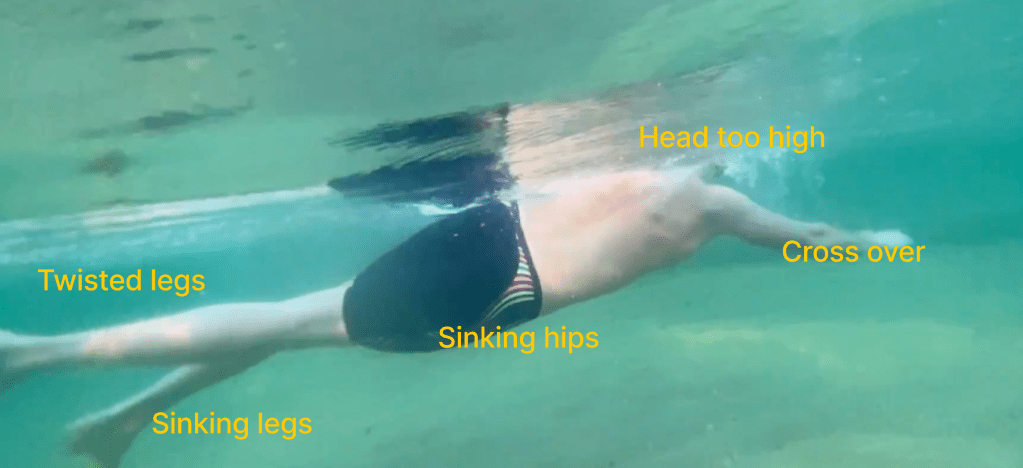

Lionel Sanders (maybe the most powerful yet least graceful triathlete)I know how to swim, but my stroke has many strange and curious habits (see above). I’m comfortable in the water, but I don’t have a great picture of what I’m actually doing in it. For example, when I kick, I don’t know what my feet are doing. I often forget that my hands cross over my body.

Also, rather than swimming smoothly, I rely on muscles to power through the water. My most dreaded swimming drill is kick board. I feel like I’m sinking, so I thrash my legs, which makes me feel like I’m sinking. Then, I get anxious that I’m holding up traffic, and I thrash even harder.

Do not frown when you read. Frowning is a symptom of the nervous muscular tension produced in and around the eyes by misdirected attention and the effort to see.

Aldous HuxleyOn Australia Day, I swam 5km in open water. It was a big distance and the water was rough, so I knew I had to conserve my energy and swim calmly. On the swim, I planned to focus on holding my head lower in the water, hopefully making me more streamlined.

After a few kilometers, it dawned on me that I was tensing my neck and back. I thought that’s what I needed to do to swim! So rather than trying to hold my head down, I stopped forcing it up, releasing these tense muscles and letting my head hang gently in the water.

I’d been so busy swimming, I’d forgotten that my body was effortlessly floating on the surface, without any added effort from me. Instead of groaning and pulling through the water, I imagined I was gently snorkeling over a beautiful coral reef. Although I didn’t suddenly start smashing PB’s and win the race, I finished feeling calm and refreshed, an achievement in itself.

I thought I was relaxed, but I was swimming like an angry man stuck in traffic. I’ve been drilling for years, yet coaching cues designed to help me relax floated over my head. So, bearing in mind the futility of words, I’ll leave you with this image to play with.

Imagine you’re lying face down in a cotton rope hammock that’s strung over a 100ft ravine. Every muscle in your body will want to tense and grab the hammock for support. Feel that tension. Now, imagine fully relaxing into the hammock. Completely release the weight of your head. Now swim.

-

Pain face

“Make friends with pain, and you’ll never be alone,”

Ken Chlouber, creator of the Leadville Trail 100

When you first start cycling, the pain you feel in your body appears to be binary. Lungs or legs. On your first proper climb, both clamour for attention. Eventually, one will speak a bit louder or persuasively, and you’ll give up. Although “it doesn’t get any easier”, your body deals with pain much differently when your fitness improves. Less weaker links. A unified front. Your body starts resembling a factory, with every organ stepping up to the assembly line and contributing to the effort.

But aside from improving your fitness, is there a way to gain a hint of control over the suffering?

Pain face

There is a point in every race when a rider encounters the real opponent and realizes that it’s…himself

Lance ArmstrongA tell for when things are getting tough, even for the best cyclists in the world, is a tightening of facial muscles, nicknamed ‘pain face’. We can’t get in their heads, but it’s clear there is some serious shouting going on in there. Jens Voigt, famous hard man explains the dialogue in third person:

Body: “I can’t do it anymore.“

Brain: “Shut up body, do what I tell you!”

Body: “I can’t do it.. I want to pull over now.“

Brain: “Keep going. I want you to do what I tell you!“

It sounds like a joke, but “Shut up legs” likely went viral because of how familiar (and painful) this inner battle is to most cyclists.

The Smiling Horse

“Everybody tells me that I never look as if I’m suffering.”

Miguel InduráinMaybe some pro cyclists possess prenatural mental skills that allow them to more easily relax under a huge workload. One example of such a rider is Miguel ‘Big Mig’ Induráin. He still endured a lot of pain, but he believed his “strength was that I am more balanced and calmer than most other riders.” Miguel had a tremendously strong physique, but maybe his mind was like a giant hay bale, and he’s essentially a galloping horse (with a horse sized heart) until the finish line. Another example of ‘relaxed effort’ is the marathon runner Eliud Kipchoge, famous for smiling while smashing records. “When you smile and you’re happy, you can trigger the mind to not feel your legs.”

Two birds, one stone

“It means quieting the endless jabbering of thoughts so your body can do instinctively what it’s been trained to do without the mind getting in the way.

Phil (six rings) JacksonSince most of us aren’t as calm or strong as Induráin, are we stuck shouting at our own legs? I’ve definitely begged and pleaded my body to do things differently, but to be honest, I’ve always felt a bit ashamed doing so. Can’t my mind and body get along? Can’t we get up the hill together?

When I’m able to fully clear my mind of distractions and pedal freely, I can hear my legs and they are usually quite happy. The legs are working: they are pistons in the engine room of the Titanic, but they are not weeping and wailing. The mind is doing the weeping and wailing for them. In fact, they are pleased with the warmth of the sun and as long as I promise them some carbs, water, and a rest in the evening, they could think of nothing else they’d rather be doing.

Mindful exercise: It’s common advice to have ‘light hands’ while climbing. A death grip can make you tense up, and use unnecessary muscles and energy. Try visualizing two baby ‘chicks’, one in each of your palms, where the hoods would be. Don’t let them go (you’ve got to return them to the mother hen at the summit), but don’t squeeze them too hard. You’ll notice your attention quickly drift off. Return to the chicks, and hopefully they are still alive when you bring them back into your attention. Repeat until you make it to the top.

-

The Wim Hof Method – Book review

The rationale of yogic breathing exercises: Practised systematically, these exercises result, after a time, in prolonged suspensions of breath. Long suspensions of breath lead to a high concentration of carbon dioxide in the lungs and blood, and this increase in the concentration of CO 2 lowers the efficiency of the brain as a reducing valve and permits the entry into consciousness of experiences, visionary or mystical, from ‘out there’.

Aldous Huxley – Heaven & Hell (1956)Long suspensions of breath, increases carbon dioxide in your lungs and blood. We’ve known the mystical effects of carbon dioxide for hundreds of years. Breath becomes a tool to change body chemistry and interface previously thought untouchable systems.

Wim asks us to change our body chemistry with breath and cold water. Wim is interesting because he has approached these practices seeking wisdom (reading the Yoga sutras in Sanskrit apparently) and walking the walk / experimenting with all his physical stunts.

But in terms of actual substance, everything aside from the ‘basic breathing technique’, is a bit cringe.

-

The shadow library

“The shadow is the self’s emotional blind spot”. You could say that your shadow is reflected unconsciously in certain things you do: your responses, your aversions, addictions, and even the books you read.

Last year I read a lot of books, including quite a bit more fiction than usual. I was looking for shorter length books, most are under 200 pages, but otherwise my criteria was very open. Anything that stood out, or looked interesting got some attention.

Individually, many of the books that I read last year are objectively good. Well written, interesting, won awards, and I finished them all – which is saying something. But combined together, they paint quite a scary, obvious picture of my shadow. I will note that although the themes of these books are depressing and dark, I rarely felt sad reading them. I didn’t even select them thinking “I’d like to read a really fucked up book today”. I suppose that’s how the shadow rolls.

In the future I think I will treat books a lot like films or any other art form. With more respect to their emotional component. In a similar way you treat a shot of high grade Tequila or a small pistol, there’s a lot of power packed into a short novel or film, and should be enjoyed responsibly.

2022 reading list, proceed with caution

South of the Border, West of Sun – Haruki Murakami Nightclub owner rips his life apart over an old flame, who might represent the void. The Factory – Hiroko Oyamada Meaningless, Kafka-esque lifetime of work in a factory. What we talk about when we talk about love – Raymond Carver Broken marriages and tense relationships, manslaughter Raised by Wolves – Jess Ho Hospitality worker didn’t like her time in hospitality Night Train – Martin Amis Suicide, Crime, Policing Kitchen – Banana Yoshimoto Grief, loss, longing, nostalgia No one is talking about this – Patricia Lockwood Impact of the internet on our generation, grief Snow country – Yasunari Kawabata Flawed, depressed businessman falls in love with a Mountain Geisha Winter in Sokcho – Elisa Shua Dusapin Eating disorders, Innkeeper in snowed in hotel, fleeting relationship with traveller Love in Big City – Sang Young Park Authenticity in age of Tinder hook ups, Homosexuality No longer human – Osamu Dazai Lonely man wears mask to get by in society, doesn’t like himself Fuccboi – Sean Thor Conroe Masculinity, relationships for millennials Whatever – Michel Houellebecq “A depressed and isolated man” -

The Terrible, Horrible Wave

“There’s never a point in surfing when you don’t have fear.”

Kelly Slater

Want to go for a surf? Before you jump in the water, be aware that the following events may happen:

- Shark attack

- Drowning

- Getting run over by another surfer

- Your board hitting someone else

- Getting ‘dumped’ by a wave and held under water

- Getting caught ‘inside‘

- Crashing into rocks

- Your board getting smashed

- Losing control of your board

- Getting in someones way, possibly starting a fight

- Rip currents

- A bad wipeout

- Getting too cold

Staring at the waves

My introduction to surfing was lying down on a foam boogie board. So, not exactly surfing, but it was still a novel, exhilarating experience. I had fun, but I sort of avoided the surfing bit. I remember paddling far out to the shoulder, where the waves weren’t breaking. I was scared. Lots of fear, not much action. Surfing (boogie boarding), was scary.

I actually have no idea what the surf instructor was trying to say here… Something about a ‘fear flower’ Since I had moved to San Francisco, I had taken up surfing, this time standing up. I had progressed a bit, but wanted more. So in 2022, I took a trip to El Salvador. I spent weeks and weeks surfing a point break, steadily improving. I took lessons. I observed others surfers, the best surfers I’ve ever seen, dance on waves with reckless abandon. I took better notice of the tides, wind, swell direction. But I was still scared. Any forward progress I made was coupled with the thought ‘I’m going to get seriously hurt.’ I was either mildly uncomfortable (if only my leash strap would stay still)… or blacked out in fear.

Not staring at the waves

“One thing you learn from surfing is how to operate in the present”

Gerry “Mr. Pipeline” LopezIn Melbourne, Australia, waves aren’t as consistent (and the water isn’t as warm) as the point breaks of El Salvador. Sometimes the wave pool is the only option to catch some waves after work. Since the pool is a controlled environment, it’s easier practice skills and try different things out.

At one point during a recent session in the pool, a surfer shouted out to his friend who was next in line “Good luck mate. 18 eyes are on ya”. On the next wave, I lost my balance and fell off. I wasn’t even the one getting trash-talked and it still affected me!

“What happened was that people felt shame more strongly and it made them angry. That affected their performance. I hadn’t expected that.”

Trash Talk can really put players off their gameAfter that wave, I decided to try an experiment. Rather than focus on turns, or the latest advice I’d heard, I blocked out all the noise. Anything that wasn’t my wave needed zero attention. By ignoring everyone else, I found it easier to remain calm, and interestingly, could surf much better. Although it felt a bit strange purposefully ignoring most of the action, I did notice some benefits.

- I caught every single wave (except the one I mentioned)

- I got many more turns than usual

- Had more fun

- Felt less tired

- Felt happier and more relaxed after the session

- Felt less stressed in the lineup

- Felt calm while I was on the wave and had bandwith to ‘think’ on the wave

- Easily navigated around a surfer who fell off in front of me (and defused situation easily afterwards)

Fear, harnessed

Is the goal to quieten the fear to nothing to surf at your best? Not quite. Tim Gallwey, sums it up nicely: “If (the surfer) wants to be in the flow, he could do that on a medium size wave. Why does the surfer wait for the big (scary) wave? The surfer waits for the big wave because he values the challenge it presents…It is only against the big waves that he is required to use all his skill, all his courage and concentration to overcome; only then can he realize the true limits of his capacities.”

Therefore, surfing should be viewed not as an exercise in quieting fear and relaxing, or a harsh battle against fear, but a ‘harnessing’ of fear to perform at your best.

-

Whole brain design

In 2023, it’s a bit passé to label an activity, person or job with ‘left-brain’ or ‘right-brain’. But most of us intuitively understand the difference. Left-brainers appear to be more organised and good with details and right-brainers thrive in creativity and innovation.

Designers lean on their right brain to empathise with people problems – “how products and services fit within people’s everyday lives as well as where they fall short, and who’s left out.”

Since the rise of consumer-friendly technology, designers have settled into the left-brain world of software, complementing the disciplines of product management (analytical and often with technical background) and engineers who ensure the systems are stable, performant, correct and maintainable.

Luckily, it’s really not so binary. Although designers are on the hook for how the product looks, we are largely concerned with making it enjoyable, learnable and effective for the user. From the tools we use like Figjam (right) and Google Sheets (left) to the skills we need like designing for emotion (right) and information architecture (left), designers need both sides of their brain firing. Xero sums it up perfectly: “You’ll have an analytical side and a knack for crafting beautiful user experiences.”

What makes product design so interesting is that there’s never a one size fits all approach to problem solving. There’s no right or wrong here. How you approach design problems will be shaped by your customers and their goals. At Xero, our payroll customers and the compliance rules they must follow are detail-oriented by definition.

All this might sound obvious, but I think friction can arise if designers don’t take the time to recognise the influence of their own thinking styles and patterns. For example, it’s not uncommon to hear a designer frustrated by “documentation slowing us down” or want to “lock down a solution asap”. These are two sides of the same coin, and might be avoided with some reflection.

Here’s a few simple questions to ask yourself:

- Do I bias more towards right or left?

- Am I uncomfortable with uncertainty (sometimes at the cost of creativity)?

- Am I avoiding (potentially useful) design methods because they are unfamiliar?

- Could I approach this problem more objectively?

- Am I thinking about this problem the same way as my cross-functional partners?

Effective designers should feel empowered to leverage either side of their brain, from beginners mind to the latest and greatest prioritisation framework. With our personal development it might help to purposefully focus some of our time on skills where we do not excel, to balance out our strengths.

By taking a step back and being intentional, we can focus on being more creative or systematic where needed.

-

Swimming with discomfort

From April – August 2020, I tried to swim very often in the sea. Usually every other day for 20-30 minutes. The trouble was the temperature of the water.

Before my swim, was a long protracted sequence of hand rubbing, swearing, dressing up in warm knits and sitting on the couch stewing in dread. It’s going to be cold.

Afterwards, although my body temperature had noticeably dropped, my body was humming and my mind felt pure.

In the middle of winter, the water would sometimes drop below 9 degrees celsius (48f).

One afternoon I went for a swim by myself. The sky was murky and brooding. The water was flat, grey and still.

When I dive in the water I usually brace myself. I clench every muscle and take on the pain that surrounds my whole body. Sometimes I claw onto a word or an image. The hope is I can distract myself away from the onslaught of sensation. Sometimes an image comes to me naturally, like a building imploding or infernal flames and smoke. To my credit, plunging your warm body into frigid water must be one of the most uncomfortable things you can do and it’s no surprise I was seeing visions of hell – that’s my base stress response putting down the hammer.

Swimming distinguishes itself from similar cardiovascular activities by the fact that your skin is completely covered by moving water rather than air. Swimming is an activity that promotes “light pressure and temperature stimulation” something that Neuroscientist Jill Bolte Taylor thinks is good for our skin, our “largest and most diverse sensory organ”. Swimming at max effort in ice water is heavy stimulation.

After the initial scream from my nocicepters, my world became water. I was in a tunnel, and I was vaguely aware of my finger tips, wrists, forearms, heels and toes going numb.

My face, covered in a neoprene hat, transitioned from burning to throbbing and kept receding into nothingness, such that it was a little hard for me to discern where my nose ended and the salty water started.

I felt fluid. I was invisible. I was a water form with some shorts and goggles strapped on. A glass submarine.

But despite this violence and unnerving stimuli, I keep going. My thoughts start wandering, and I’m wondering, am I actually cold anymore?

I must be cold.

I swim a little further and make it to a yellow marker. I’ve swum further and faster than I expected, and I realize if I swim back at the same speed I’d have been in the water for over half an hour – too long.

As I tread water, mulling logistics, I finally pay attention to my surroundings. I notice a ghostly quiet that has settled on the entire beach. The beach huts, the pale sand, ripples near my fingers. In every direction nothing but a grave stillness. I can’t see the separation between sky and sea and I can’t feel the separation between the sea and my body.

I look down at my legs below and realize I’m looking at my body from a slightly higher vantage point.

My brain explains to me that I’m fucked: (“I’ve got hypothermia”, “I’m going to die”, “I need to go home as soon as possible”). But my body has disconnected the phone line and has started playing light jazz. My sympathetic nervous system resembles a sauntering Robert Duvall in Apocalypse Now.

The experience is disconcerting mainly because of how ‘opposite’ it is to how I know I should be feeling. This is a good example of how the stories we tell ourselves are so powerful they can overwrite even the most shocking and obvious physical experiences. “This is wrong” rings so true in my mind, I simply have to listen.

A few hours later, I’m dried off and warm but I’m a bit dazed and confused and mellow. I chalk it up to a severe loss in body temperature. But maybe the cold water wasn’t so bad. Maybe my body was perfectly happy to swim in cold temperature. It’s not crazy to believe my body was actually excited by the novel, stimulating sensation of cold water once in a while. I think it’s helpful to think of our bodies both objectively and with great gratitude, like a big gentle dog always by our side.

Most people know, logically, that discomfort is an inevitable part of life. But experientially, we fail to accept this fact, and our desire to flee from it compounds our suffering. If we can learn to witness discomfort without fighting it, we weaken its hold on us, bolstering our ability to lead stable, satisfying lives.

The Mindful Case for Cold ShowersAlthough memorable, this was a just one swim among many hundreds of hours in the ocean and pool. Aside from the obvious health benefits, swimming in cold water seems to train us to sit with discomfort.

Next time you go for an ocean swim, or even simply turn the shower a bit colder, try to pierce through all that screaming for comfort, you may not actually need it after all.

-

The time Murakami ran 62 miles

The following is an excerpt from the book “What I Talk About When I talk about Running” by Haruki Murakami. He’s running an ultra-distance race.

While I was enduring all this, around the forty-seventh mile I felt like I’d passed through something. That’s what it felt like. Passed through is the only way I can express it. Like my body had passed clean through a stone wall. At what exact point I felt like I’d made it through, I can’t recall, but suddenly I noticed I was already on the other side. I was convinced I’d made it through. I don’t know about the logic or the process or the method involved—I was simply convinced of the reality that I’d passed through.

After that, I didn’t have to think anymore. Or, more precisely, there wasn’t the need to try to consciously think about not thinking. All I had to do was go with the flow and I’d get there automatically. If I gave myself up to it, some sort of power would naturally push me forward.

Run this long, and of course it’s going to be exhausting. But at this point being tired wasn’t a big issue. By this time exhaustion was the status quo. My muscles were no longer a seething Revolutionary Tribunal and seemed to have given up on complaining. Nobody pounded the table anymore, nobody threw their cups. My muscles silently accepted this exhaustion now as a historical inevitability, an ineluctable outcome of the revolution. I had been transformed into a being on autopilot, whose sole purpose was to rhythmically swing his arms back and forth, move his legs forward one step at a time. I didn’t think about anything. I didn’t feel anything. I realized all of a sudden that even physical pain had all but vanished. Or maybe it was shoved into some unseen corner, like some ugly furniture you can’t get rid of.

Since I was on autopilot, if someone had told me to keep on running I might well have run beyond sixty-two miles. It’s weird, but at the end I hardly knew who I was or what I was doing. This should have been a very alarming feeling, but it didn’t feel that way. By then running had entered the realm of the metaphysical. First there came the action of running, and accompanying it there was this entity known as me. I run; therefore I am.

And this feeling grew particularly strong as I entered the last part of the course, the Natural Flower Garden on the long, long peninsula. It’s a kind of meditative, contemplative stretch. The scenery along the coast is beautiful, and the scent of the Sea of Okhotsk wafted over me. Evening had come on (we’d started early in the morning), and the air had a special clarity to it. I could also smell the deep grass of the beginning of summer. I saw a few foxes, too, gathered in a field. They looked at us runners curiously. Thick, meaningful clouds, like something out of a nineteenth-century British landscape painting, covered the sky. There was no wind at all. Many of the other runners around me were just silently trudging toward the finish line. Being among them gave me a quiet sense of happiness. Breathe in, breathe out. My breath didn’t seem ragged at all. The air calmly went inside me and then went out. My silent heart expanded and contracted, over and over, at a fixed rate. Like the bellows of a worker, my lungs faithfully brought fresh oxygen into my body. I could sense all these organs working, and distinguish each and every sound they made. Everything was working just fine. People lining the road cheered us on, saying, “Hang in there! You’re almost there!” Like the crystalline air, their shouts went right through me. Their voices passed clean through me to the other side.

I’m me, and at the same time not me. That’s what it felt like. A very still, quiet feeling. The mind wasn’t so important. Of course, as a novelist I know that my mind is critical to doing my job. Take away the mind, and I’ll never write an original story again. Still, at this point it didn’t feel like my mind was important. The mind just wasn’t that big a deal. Usually when I approach the end of a marathon, all I want to do is get it over with, and finish the race as soon as possible. That’s all I can think of. But as I drew near the end of this ultramarathon, I wasn’t really thinking about this. The end of the race is just a temporary marker without much significance. It’s the same with our lives. Just because there’s an end doesn’t mean existence has meaning. An end point is simply set up as a temporary marker, or perhaps as an indirect metaphor for the fleeting nature of existence. It’s very philosophical—not that at this point I’m thinking how philosophical it is. I just vaguely experience this idea, not with words, but as a physical sensation. Even so, when I reached the finish line in Tokoro-cho, I felt very happy. I’m always happy when I reach the finish line of a long-distance race, but this time it really struck me hard. I pumped my right fist into the air. The time was 4:42 p.m. Eleven hours and forty-two minutes since the start of the race.

What I Talk About When I Talk About Running (Vintage International) (pp. 111-115). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

-

Eating until you are 100% full

No man has the right to be an amateur in the matter of physical training. It is a shame for a man to grow old without seeing the beauty and strength of which his body is capable.

SocratesFor the past 6-12 months, on average, I:

- Slept for 7 hours and 35 minutes per night

- Consumed 3152 calories of food per day

- Consumed 161g of protein per day

- Weighed on average 88.47kg per day

- Burned 1100 calories above my resting rate per day

I should celebrate these numbers. I was consistent. I built new habits and stuck to them. I thought carefully about what I ate and how I moved my body. I rarely got sick, maintained my goal weight and smashed tons of PB’s on the bike and in the pool. Isn’t this what success looks like?

The moment you arrive at it, it begins to recede, because you’ve got all these other goals on the horizon.

Sam HarrisMaybe not. Counting my ZZZ’s and my calories didn’t make me happy. It didn’t make me feel better about myself or push me into new, interesting paths in life. I measured because it was easy and it made me feel good (temporarily). My BMI was low and steady, a common standard for good health, but only because I was feverishly modulating my energy intake. The measure “ceases to be a good measure”.

A few months ago, after some reflection, I decideded to press pause on the quantified self. Ironically, despite amassing thousands of data points and colorful charts, the biggest insight arrived once I stopped. I noticed a lot of negative self talk. “You’ll lose muscle.” “You’ll lose progress.” “You won’t think straight.” “You should watch this video and try this diet instead.” “You’ll get more anxious if you don’t eat as healthy.” “You will be grumpier if you don’t sleep.”

Maybe I should listen to this voice. Or rather, maybe I should continue obeying. Maybe I should plan out the next 16 meals in perfect synchrony. Maybe I should listen to this 2 hour lecture about carbohydrates. Maybe fasting is the answer. Maybe… Or maybe not. I realized that the foundation of my routine was a voice of non-reason. I was disheartened, humbled and motivated to try a completley different approach in the future. This path had reached its natural conclusion.

The unexamined life is not worth living

Socrates, againThere’s obvious benefits from tracking your food, exercise and sleep. I’m grateful a (much fitter and more successful) colleague encouraged me to be mindful of the proteins, carbs and fats that made up every bagel and $1 slice of pizza that I was stuffing into my face circa 2014. With enough examination, you’ll learn the types of foods that your body digests well and that make you feel good. You’ll learn how to lose weight quickly and safely rather than the typical yo-yo of death. You’ll learn how to put on lean muscle and keep it. And many other useful habits and insights that only come from tinkering and practice.

There are no shortcuts. The fact that a shortcut is important to you means that you are a pussy.

Mark RippetoePeering at the nutrition label to find the fiber values, selecting the ‘best’ peanut butter with no seed oils, determining the exact macronutrient profile of rotisserie chicken. These are all things I’ve done too many times. This might feel more ‘examined’, but I can assure you it’s got nothing to do with mindfulness. It’s scarily normal for someone counting calories to nervously mix up a protein shake or scarf down a plate of lunch meat to hit some arbitrary goal. There’s nothing mindful about that.

If you’re thin, you are a kook; if you’re fat, you’re a failure.

Lionel ShriverEating healthy and losing weight is incredibly hard for many people. I know because I’ve seen the data firsthand, both from talking to hundreds of average Americans about their goals and problems and by understanding how millions of people used MyFitnessPal every day. Everything from the government to your home environment can feel like it’s working against you, let alone your thoughts and bad habits. So, most people eat like crap, sleep like crap and hardly move. The World Obesity Atlas 2022, predicts that one billion people globally, including 1 in 5 women and 1 in 7 men, will be living with obesity by 2030. This is a problem worth solving. I’m grateful I have access to real food and the time and energy to be intentional about my habits, but I can’t say that incessant tracking is the answer.

Where does that leave me? Well, I haven’t yet chucked out my weight scales (I don’t think we’re very good at eyeballing our own weight). I haven’t changed my training schedule. I’m still interested in lots of food-related things, from mastering the Puttanesca to the concept of Hara Hachi bun me (腹八分目) – eating until you’re 80% full. But for the calorie tracking, it was IN for a while, now it’s OUT.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.