“A huge percentage of the stuff that I tend to be automatically certain of is, it turns out, totally wrong and deluded.”

— David Foster Wallace

Whether you are making shoes, advertisements about shoes or shoe-making software, it’s likely the work is getting done in a group or a team.

Since 2020, this way of working has become especially important. Engineers and designers can no longer reliably chat at a desk or gather around a whiteboard. Those conversations have migrated online to collaborative software, like Miro and Figma.

If you’re used to working alone, it can be overwhelming to see all this work in progress. Miro boards filled with sticky notes, spaghetti diagrams, screenshots and other design detritus. What used to be private thinking is now facilitated in real-time workshops, with dozens of stakeholders calling in, watching, listening and co-designing together.

I resisted this type of collaboration for a long time.

I was critical of workshops and dismissed them as “UX theatre”. I thought they were inefficient and believed there was better ways to use my time. I didn’t think stakeholder management was my job. I was wary of politics, group think and other barriers to creativity. And when I had no other choice, I turned my criticism inward, lamenting my own facilitation skills or introversion. I thought, maybe I’d like collaboration if I was actually good at it.

There might have been some truth to these concerns. But what if it was less about collaboration being a mess, and more about my own need to be perfect?

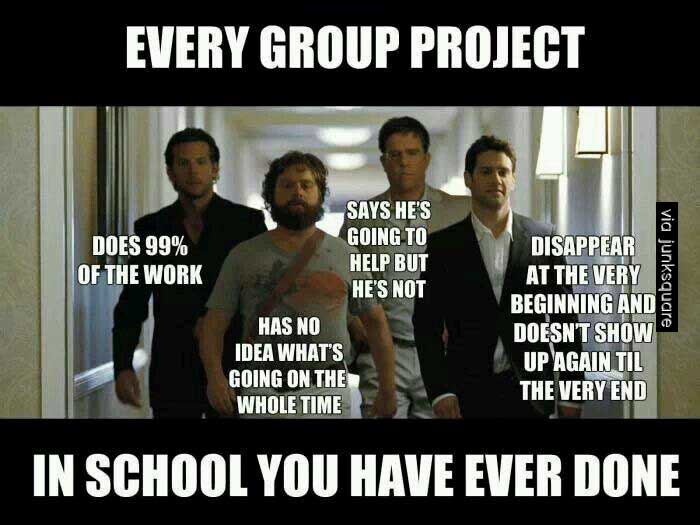

Anti-teamwork

A perfectionist is usually defined as someone who has set high standards for themselves or others. At their core, they need to look good and be right. And at first glance, a perfectionist in the team will look like and sound like a normal person. They’ll bring their skills, help out and try to work together. But because of this strong, often unconscious need, they tend to prevent, rather than encourage healthy collaboration.

Firstly, a perfectionist cares more about how they look, rather than the shared goal of the team. They’ll often lose sight of the overall goal, and instead tend to focus on little things that don’t really make much difference.

The perfectionist is usually driven by a harsh ‘inner critic’ that nags and nitpicks them hundreds of times before they critique or blame another person. But when they do, harsh criticism will make their team feel judged, shamed and less likely to share ideas. Hypocritically, a perfectionist can’t bear to be criticized.

A perfectionist thinks they are right. This rigid conviction comes at the cost of creativity, listening and general respect for others. If you believe you are right about something, why listen to someone else? Conviction taken to extremes is behind every totalitarian regime and fundamentalist religion. Due to their predictable righteousness, a perfectionist will struggle to sit with uncertainty, ambiguity without an “irritable reaching for facts and reason.”1

A perfectionist can’t handle being ordinary. They think in black and white terms; their output is trash that needs to be exceptional. They live in a fantasy world and need to return to reality, where the rest of their team is waiting. Marie-Louise Von Franz connects this attitude with a “sudden-fall” dream, which she says “generally coincide with outer, deep disappointment when one is suddenly faced with naked reality as it is.”2

Lastly, a perfectionist doesn’t know how to fail. If something doesn’t turn out how they planned, they blame or find ways to avoid responsibility. Without owning (and learning) from these mistakes, they have failed to fail, or what I’m coining inauthentic failing. They’d be better off to “get back up… to celebrate behaving like a human—however imperfectly—and fully embrace the pursuit that you’ve embarked on.”3

It’s easy to wave off perfectionist tendencies if you’ve got them. I’d filed most of mine under positive sounding interview answers like attention to detail, working too hard or caring a bit too much.

Collaboration can be chaotic. For a perfectionist, this collaborative world can feel like hell and they naturally want to defend against it viciously. That’s where all the ranting, blaming and burning the midnight oil comes from.

But rather than blame brainstorming or lame ice-breakers, I would have been better off noticing my own perfectionism – and how it makes collaboration nearly impossible.

To truly collaborate, and to actually get things done, one must accept the messy Miro board, the antithesis of perfection, the ordinary, imperfect nature of life itself.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Negative_capability ↩︎

- Marie-Louise von Franz, The Way of the Dream: Conversations on Jungian Dream Interpretation ↩︎

- Marcus Aurelius, Meditations ↩︎